A feature story by Jennifer Selby

You see the queue first, snaking around the corner. Then a low thrum of voices: German, Polish, Romanian, some Lithuanian, their speakers silhouetted by their breath. Security guards stand watch as battered suitcases and tattered plastic bags shuffle along their nightly route. Occasionally there is a scuffle. It is 7:45pm.

This is a familiar scene for all those who know Berliner Stadtmission’s emergency overnight shelter on Lehrter Straße, near Berlin’s Hauptbahnhof. Here, every evening people arrive in search of food, shelter, clothing, and medical care.

What people seek above all is warmth. However this year, it is in short supply. As temperatures plummet below zero for the first time this winter, shelters like this one are facing a “perfect storm” of rising energy costs and decreased donations, while demand for support is greater than ever.

“We are seeing demand growing across the city. More and more people are coming,” says Barbara Breuer, a spokesperson for the charity.

Berliner Stadtmission is just one in a network of non-profit organizations scrambling to provide low-threshold, around-the-clock cold aid to the estimated 2000 people facing winter on the streets of Berlin. With over 90 social projects, Berliner Stadtmission is one of the biggest social aid providers in the city.

While costs vary from project to project, the price of heating and running shelters like this one have risen by “up to 50%” from this time last year, according to Barbara. Meanwhile, cost of living pressures mean much-needed donations are at an all-time low.

“I don’t think that the people giving to us are rich usually, they just want to do something good and help others,” says Barbara. “But if people don’t have money themselves, they can’t give it to anyone else.”

While the Senate has provided some financial relief, it doesn’t cover all the costs, and things like food, counseling and medical care rely solely on donations. According to Barbara, these are the things that make the difference.

“The people that come to us need medical care and counseling. It’s not enough to give them a key and a place to sleep on the floor if you want to get them out of their situation,” says Barbara.

Berliner Stadtmission’s main food supplier, Tafel, which provides food to 400 social facilities, food banks and cold facilities across the city, is also facing unprecedented demand, reporting “more than 100% growth at almost all distribution points”. Tafel themselves are suffering shortages from corporate donors, while they fear energy costs will make a bad situation worse.

“What we will all find very difficult to bear is the price increase that will come in the utility bills,” said Sabine Werth, chairwoman of Tafel, to RBB Inforadio this week. “I’m looking forward to very bad times again.”

The reduction in food donations puts strain on services that are already overstretched. This shelter on Lehrter Straße officially accommodates 125 people, but every night this season they have admitted closer to 160. Some people queue from 3pm to guarantee a space. Latecomers sleep on the cafeteria floor.

“Usually the busy period is between 8-11pm,” says Dasza, 25, a Berliner Stadtmission volunteer, who is shivering despite her thick waterproof jacket. “But on cold nights like this people just keep coming and coming.”

Nevertheless, Dasza explains, they cannot turn anyone away.

“We can’t leave them outside. They might freeze to death,” she says, pointing a gloved hand to a sign that reads: ‘No Drinking, No Drug Use, No Discrimination, No Knives, No Violence’.

“When it’s cold, people are more stressed and more dangerous. Often they are alcoholised, because that’s how they get by. But so long as they follow the rules, they can come in.”

Originally from Russia, Dasza is fluent in five languages. She explains her language skills are invaluable here, where many visitors don’t speak German.

“Many people don’t have documents. We have doctors and counselors here every evening and it doesn’t matter whether you have medical insurance or not.” she says, adding: “We get people here that have nowhere else to go.”

At 8pm, the doors open and the first people trickle through. From a steel kitchen counter, they collect warm potato soup in paper cups and pastries that are still good to eat. The mood thaws. There are smiles and laughter, nods of recognition. Some retreat to their regular spots along thin wooden tables. Wearier guests head straight to a church pew where they can get first in line for a bed to rest before 7am when they will be back out on the streets.

During the day, there are various services in the cold aid network that provide showers and laundry facilities as well as food, hot drinks and shelter. At these places, it is not just homeless people that are contributing to the increase in demand.

“We are seeing more people coming who have a place of residence but are on the poverty line,” says Barbara. “More people visit our hygiene stations towards the end of the month when their bills are due.”

Barbara says they have particularly seen an increase in elderly women at their city stations that provide a free hot lunch. “They have some money – they have their pension – and they used to make it work out, but they just can’t cope with the rising prices.”

Regrettably, they have had to start turning people away.

The situation is exacerbated by volunteer shortages, which drove the charity’s largest shelter by Bahnhof Zoo to drastically reduce its hours last month, on some weekends closing altogether.

Meanwhile, a fire at the air dome homeless shelter in Friedrichshain forced the urgent relocation of some 120 people.

Berliner Stadtmission has been appealing for donations in kind to redress the shortages during this period, especially food, sleeping bags, and warm winter clothing.

As the first cold deaths are reported, The Federal Working Group for Homeless Aid (BAG W) in Germany calls on municipalities to be more actively involved in protecting the homeless from the cold, and to suspend forced evictions during winter.

“The possibilities of emergency response facilities are not endless,” says Werena Rosenke, Managing Director of BAG W. “Now the municipalities are required, but also every single citizen. Together we must pay attention to those who cannot help themselves and have to live without a home or shelter. Every death is one death too many.”

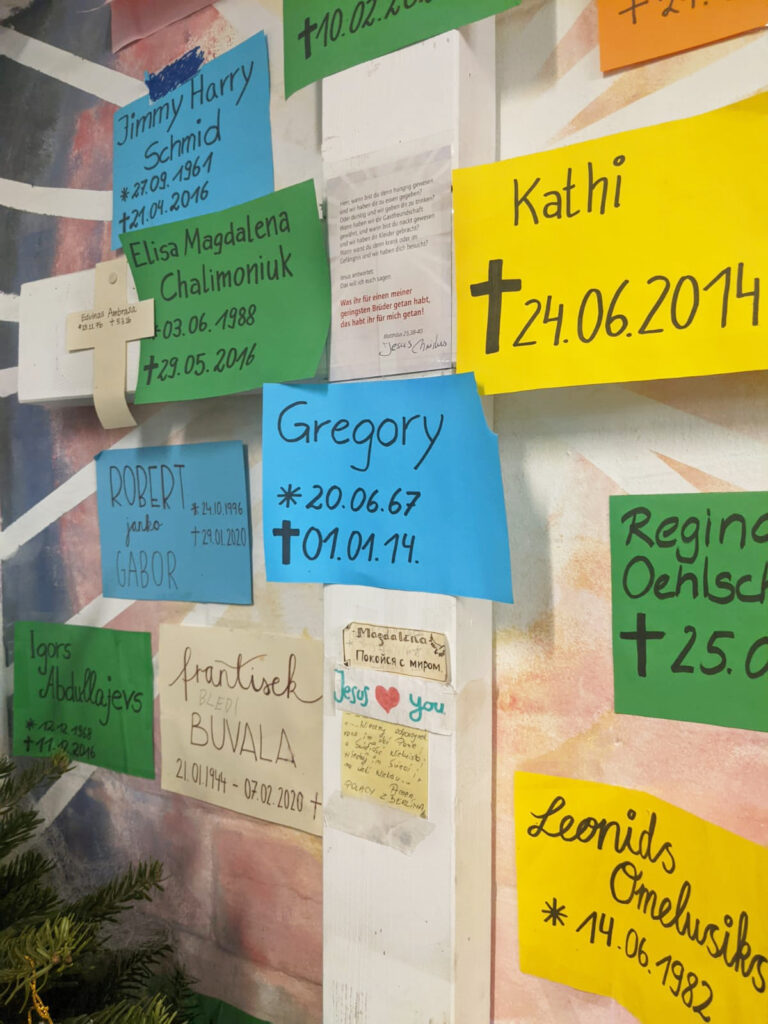

At the Lehrter Straße shelter, they are preparing for Christmas. Origami stars and snowflakes made from old magazines hang from exposed air ducts that line the low basement ceilings. In one corner, a heavily adorned Christmas tree brings some warmth to the room. Above it, there are scraps of A4 paper in yellow, blue and green, scribbled with names – Kathi, Aurel, Sandra, Marcin – and dates: 1980 – 2020; 24.06.2014; May 2021; 02.10.1985 – 03.05.2016.

“They are prayers for people who used to come here,” explains Dasza. “Some of them died in the queue.”